Bloopers: Living Labs Report - Part 2: Typology of Living Labs

Living Labs come in many shapes and forms. This post aims to tease out some of the different forms to better understand their strengths and focuses to advance how we build and sustain Labs over time.

This is Part 2 in a series of posts after the publishing of 'Advancing University Living Labs: relational infrastructure for transformative impact', with some outtakes which didn't make the final report, but I still want to share.

You can read Part 1: Generations here.

Context

What are Living Labs? Simply put, they're platforms for change; bringing together people from across government, business, civil society, academia and more, to co-create ways to address the challenges of our time.

Find out more:

Background

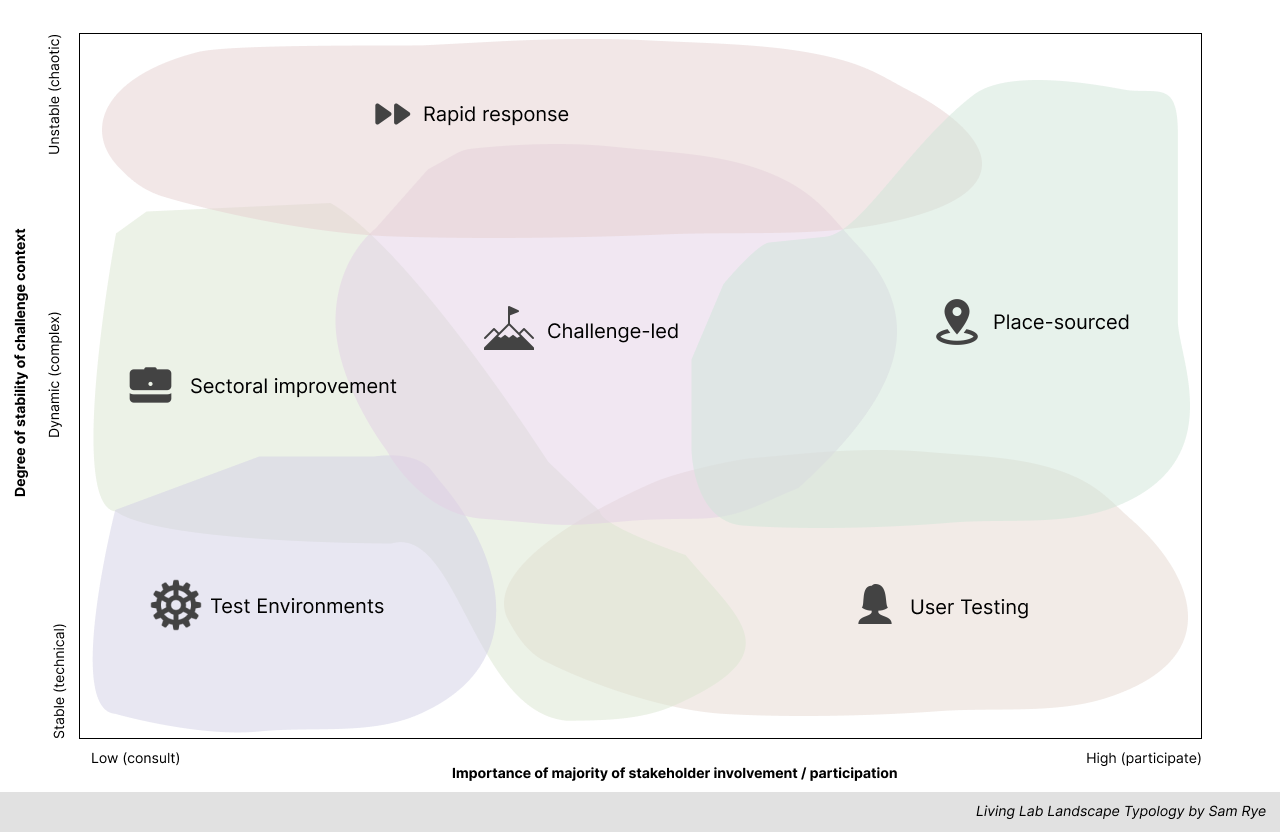

Living Labs come in many shapes and forms - making strategic choices about the type of living lab that is being developed is key to ensuring the clusters of capabilities, key partners to crowd in, geographic boundaries, process model, scale of resources needed and ongoing financial model are fit for purpose.

These are not meant to be mutually exclusive types, instead I aim to tease out different shapes of living labs with the intention to support more nuanced conversations early on, or at maturing transitions in the evolution of labs.

There have been various proposed Living Lab typologies, [1] [2] [3] [4] however, the diversity of forms of Living Labs and their associated practice is evolving at such a rate that I believe an updated typology is needed.

The following typology has been proposed to be accessible to people and organisations who may be less familiar with Living Labs yet are also convening, funding and partnering to tackle complex challenges. The typology is based on the case studies in the Monash University Advancing University Living Labs report [6] as well as research and engagement with Living Labs around the world.

The typology spans technical and ‘complicated’ challenges (such as developing a decentralised energy system), complex challenges (such as achieving sustainable mobility for a town) and into ‘chaotic’ or unstable challenges (such as pandemic response), framed around the Cynefin sensemaking framework. [5]

Living Labs are categorised in this typology by their primary characteristics, whilst recognising that they may include elements of other types), thus presenting the landscape view with overlaps.

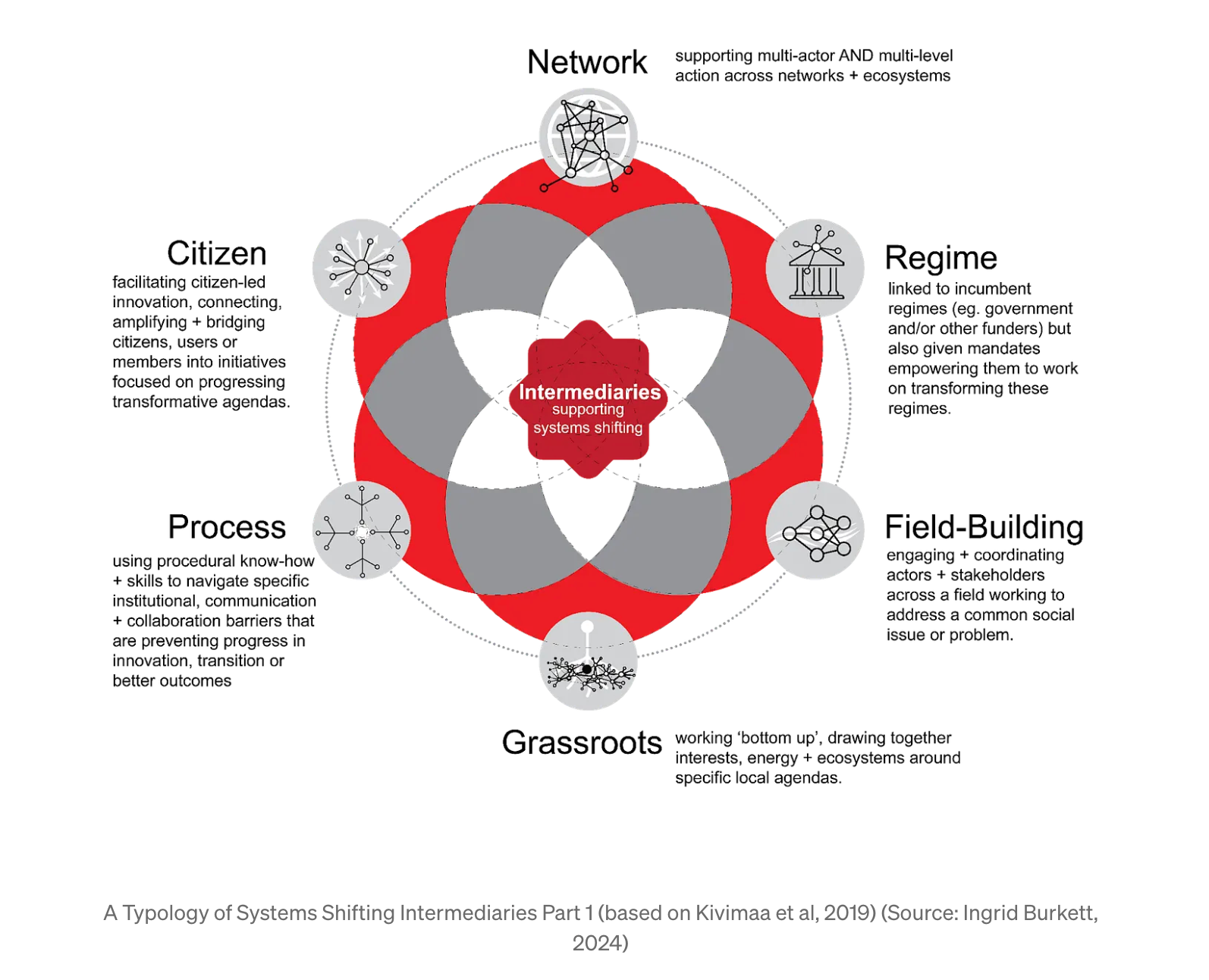

Living Labs are considered in this typology as intermediaries, hence the inclusion of the ‘systems shifting intermediaries’ functions. [7]

Example: a Challenge-led Living Lab focused on net zero emissions will have one or multiple places in which their activities are conducted - whilst these places are important to the lab’s challenge, they are enablers not the primary focus. Whereas, a Place-sourced lab focusing on a specific town or region may have net zero as a project or cluster of activity, but will likely look at connected challenges such as local economic development, health and wellbeing or local transport.

A landscape typology for Living Labs

The Living Lab Typology - Detail

User Testing

- Type of challenge: Technical or Complicated

- Example: Developing service model for Micro-mobility sharing scheme

- Focus: assessing user & market validation through prototyping and testing of solutions.

- Typical Form: Business & Academia research / enterprise partnerships

- Participation orientation: People as research subjects or collaborators

- Intermediary functions: Process, Regime

Test Environments

- Type of Challenge: Technical or Complicated

- Example: Developing a distributed Energy System

- Focus: physical environments and data, utilised for improved efficiency, data-informed decision making, and innovation stemming from the data streams & observations.

- Typical Form: Industry - Academic Partnerships

- Participation orientation: Partners as collaborators

- Intermediary functions: Process, Regime

Sectoral Improvement

- Type of Challenge: Technical or Complicated / Complex

- Example: Advance sustainable agriculture practices

- Focus: exploring new products, services, supporting infrastructures and strategies to advance sectoral improvement

- Typical Form: Industry - Government - Academic Partnerships

- Participation orientation: Partners as collaborators

- Intermediary functions: Process, Regime

Place-sourced

- Type of Challenge: Complex

- Example: Regenerating an urban neighbourhood

- Focus: public or societal impact, utilising learning & adaptation, co-creation sourced and deeply rooted in and sourced-from a specific place. Cross-sectoral open innovation with a portfolio of solutions / initiatives.

- Typical Form: Coalition or place-based initiative between Civil Society, Community, Government, Academia, Business

- Participation orientation: Partners, Citizens and Stakeholders as empowered participants and collaborators.

- Intermediary functions: Citizen, Network, Regime, Field-Building, Grassroots, Process

Challenge-led

- Type of Challenge: Dynamic or Complex

- Example: Net Zero in a region

- Focus: directional, coherent, co-ordinated collective action. Working on bounded systems or ambitious goals with partners from across all sectors.

- Typical Form: Transformation initiative or contributor to Mission-oriented policy or strategy between Government, Business, Civil Society, Academia

- Participation orientation: Partners, Citizens and Stakeholders as empowered participants and collaborators.

- Intermediary functions: Citizen, Network, Regime, Field-Building, Grassroots, Process

Rapid Response

- Type of Challenge: Unstable or Chaotic

- Example: Food sector supply chain response to Covid-19

- Focus: organising across a sector or system to respond to rapid transitions in times of relative instability. Outcomes may involve sectoral reorganisation, recommendations, or temporal initiatives, etc.

- Form: Government, Business, Civil Society

- Participation: Response-focused Partners as empowered participants, citizens to be informed.

- Intermediary functions: Regime, Field-Building, Process

Conclusion

This typology aims to bring some nuance to the discussion about how we orient, design and implement labs as responses to societal challenges.

We could look at this through the lens of Generations of Living Labs and understand that as the field has matured, orienting towards more complex challenges from the early roots of technical and complicated challenges has been a natural evolution.

Fundamentally, Labs which focus on technical challenges will operate and have quite different Capabilities, different resource needs, and different financial models for sustainability, from ones focused on complex challenges.

Nuancing our conversations about the kinds of Labs we're building and working on is an important part of better understanding different aspects of Living Lab (and Social Innovation Lab) research, education and practice.

As always - keen to hear your thoughts here or over on Linkedin, happy to be challenged, and keen to discuss!

Next Steps

The next post couple of posts will take a dive into the origins of different Labs, as well as a way to consider the maturity pathways for Labs to move from simple demonstrations to platforms for change over time, grounded in the likes of innovation ecosystems and transitions theory.

References

[1] Hossain, M., Leminen, S., & Westerlund, M. (2019). A systematic review of Living Lab literature. Journal of cleaner production, 213, 976-988.

[2] Schuurman, Dimitri & Mahr, Dominik & Marez, Lieven & Ballon, Pieter. (2013). A fourfold typology of Living Labs: an empirical investigation amongst the ENoLL community. ICE & IEEE-ITMC- ldots.

[3] Alavi, H. S., Lalanne, D., & Rogers, Y. (2020). The five strands of Living Lab: A literature study of the evolution of Living Lab concepts in HCI. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 27(2), 1-26.

[4] Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., & Nyström, A. G. (2012). Living labs as open-innovation networks.

[5] Snowden, D. (2005). Strategy in the context of uncertainty. Handbook of Business strategy, 6(1), 47-54.

[6] Rye, S., Donaldson, L., French, M., Jasieniak, J., & Raven, R. (2025). Advancing University Living Labs: Relational Infrastructure for Transformative Impact (Version 1). Monash University. https://doi.org/10.26180/30653942.v1

[7] Burkett, I. (2024) Governance in and for complexity: Part 1: collective governance within intermediary organisations. Good Shift. Accessed at: https://medium.com/good-shift/governance-in-and-for-complexity-eac108d8b589