Furthering Experimentation Practice - Part I

Lately I've been thinking about the capabilities, process and frameworks needed for effective change work, as a continuation of a theme which has run through my work for 10+ years now - experimentation.

"No person steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and they're not the same person."

- Adapted from Heraclitus

In my role at Monash University, we're exploring the role of 'living labs' and relational infrastructure for catalytic change, and creating spaces for multi-stakeholder engagement and experimentation.

I'll share more about this work as I can, but in the meantime it got me thinking about different modes of experimentation, what good practice looks like, and opportunities for it to be used more.

Context

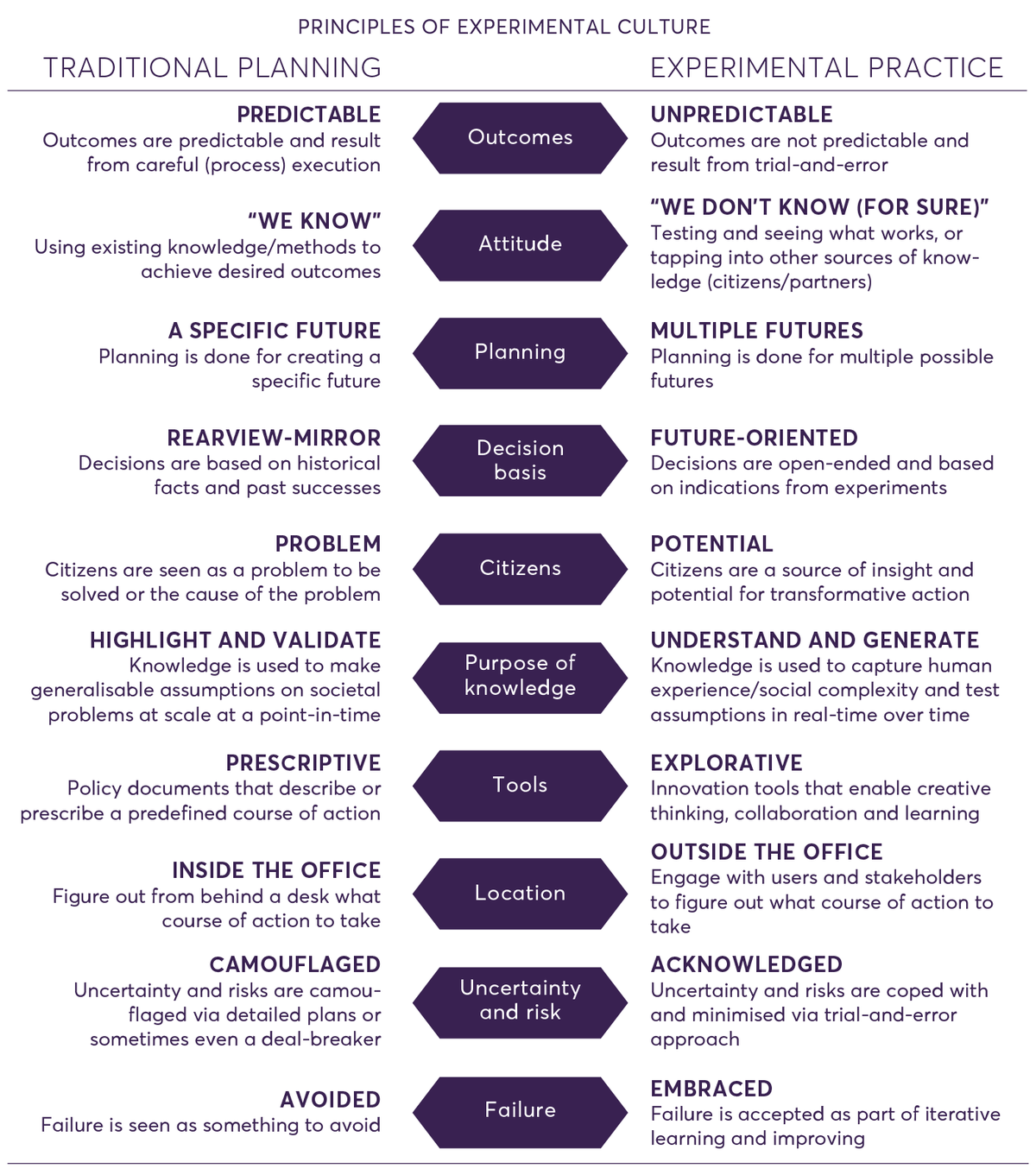

Let's back track a little. When I'm talking about experimentation, I'm not talking about lab benches and microscopes, so much as a process of 'experimenting-to-learn', as distinct from 'analysing-to-precict' which characterises Planning approaches to change.

When I first started writing about this nearly 10 years ago, my thinking was influenced by social entrepreneurship of the time, however my practice has diverged significantly from the 'riskiest assumption' / market-led simplicity, and is honed much more towards the exploration of complex social and environmental challenges of the age.

As the incoherence of linear planning and single point solutions with issues like climate change or rapid urbanisation become increasingly apparent, organisations are starting to explore “portfolio approaches” as a way to better come to grips with complexity.

- UNDP Asian Pacific (Regional Innovation Centre) - Portfolio approaches to tackle complex problems

This "portfolio-of-experimentation" is an increasingly necessary and accepted approach to change work (e.g. in the Government context, in multi-stakeholder living labs, in urban transitions, and in food systems), as we accept the implications of complexity science. Complexity science shows us change cannot be controlled, that how systems respond cannot be predicted acurately, and that the constant is change - meaning the same intervention will have different results over time / context.

[side note: to understand more about this, you can read my series "The so what of complexity" here: posts one, two and three]

As I've spoken to people about experimentation culture and practicalities over the years as a response to work in and with complexity, the common pattern is that people ask "where would I start?!".

An Experimentation Continuum

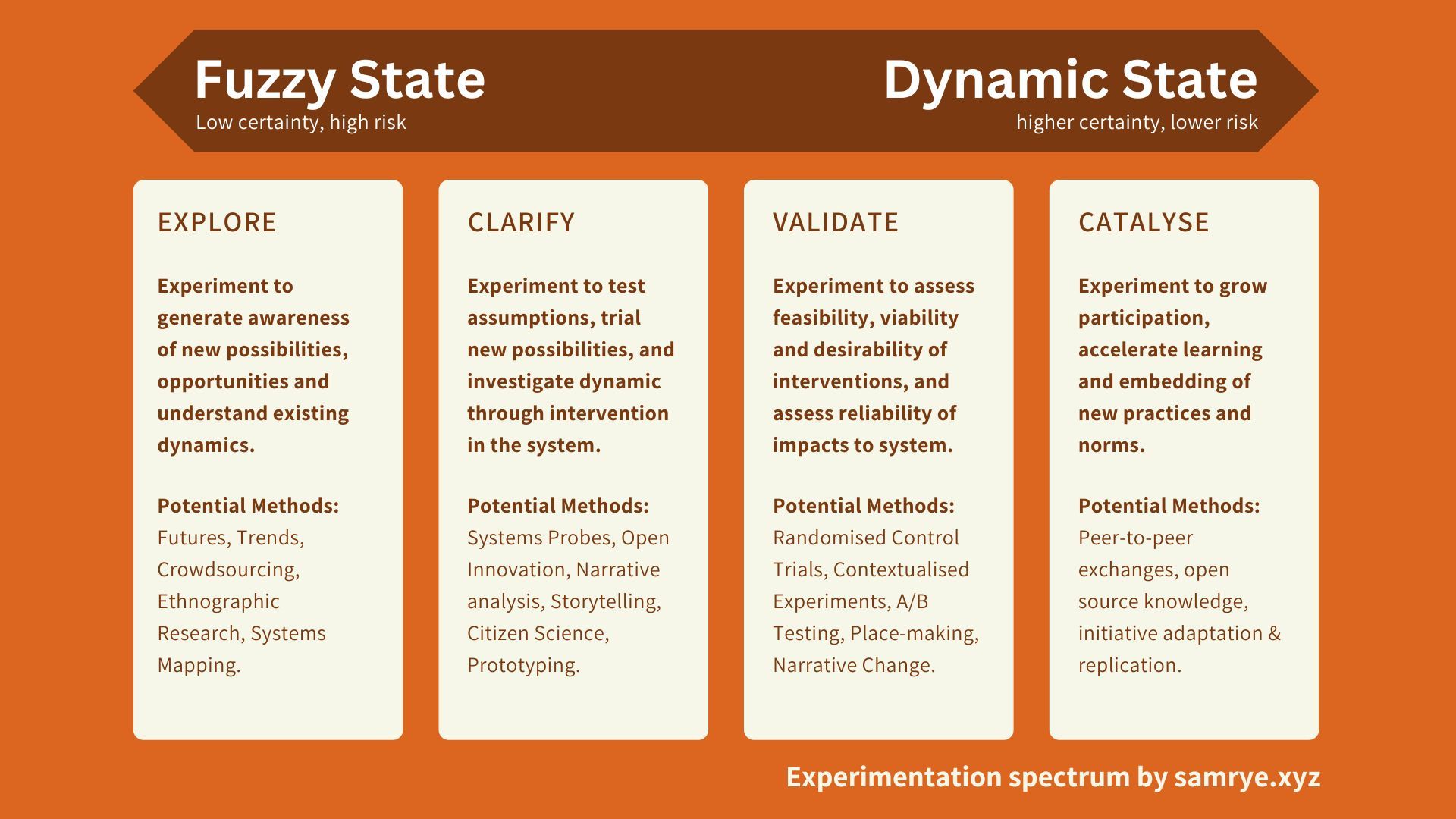

This brings me to the first element to address - experimentation practice can be used across a spectrum, each of which modes may have a slightly different focus and goal.

Inspired by and adapted from Bas Leurs' excellent Experimentation Continuum from "Towards an experimental culture in government: reflections on and from practice" over at Nesta, here's a revised experimentation continuum as a starting point.

To understand where to start with experimentation, you need to situate yourself somwhere on the continuum, to know what kinds of methods and goals you might have.

This is a work in progress, but blends the work from Nesta, with insights from an interesting paper from the Living Labs world (Toffolini et al, 2023) which highlighted the importance of experimentation as a Catalyst for longer term collective action.

Directionality and Prioritisation

Secondly, we need to understand directionality and prioritisation. If people, groups or organizations start “just experimenting” without properly considering what they are trying to achieve, the value of experimentation is diminished.

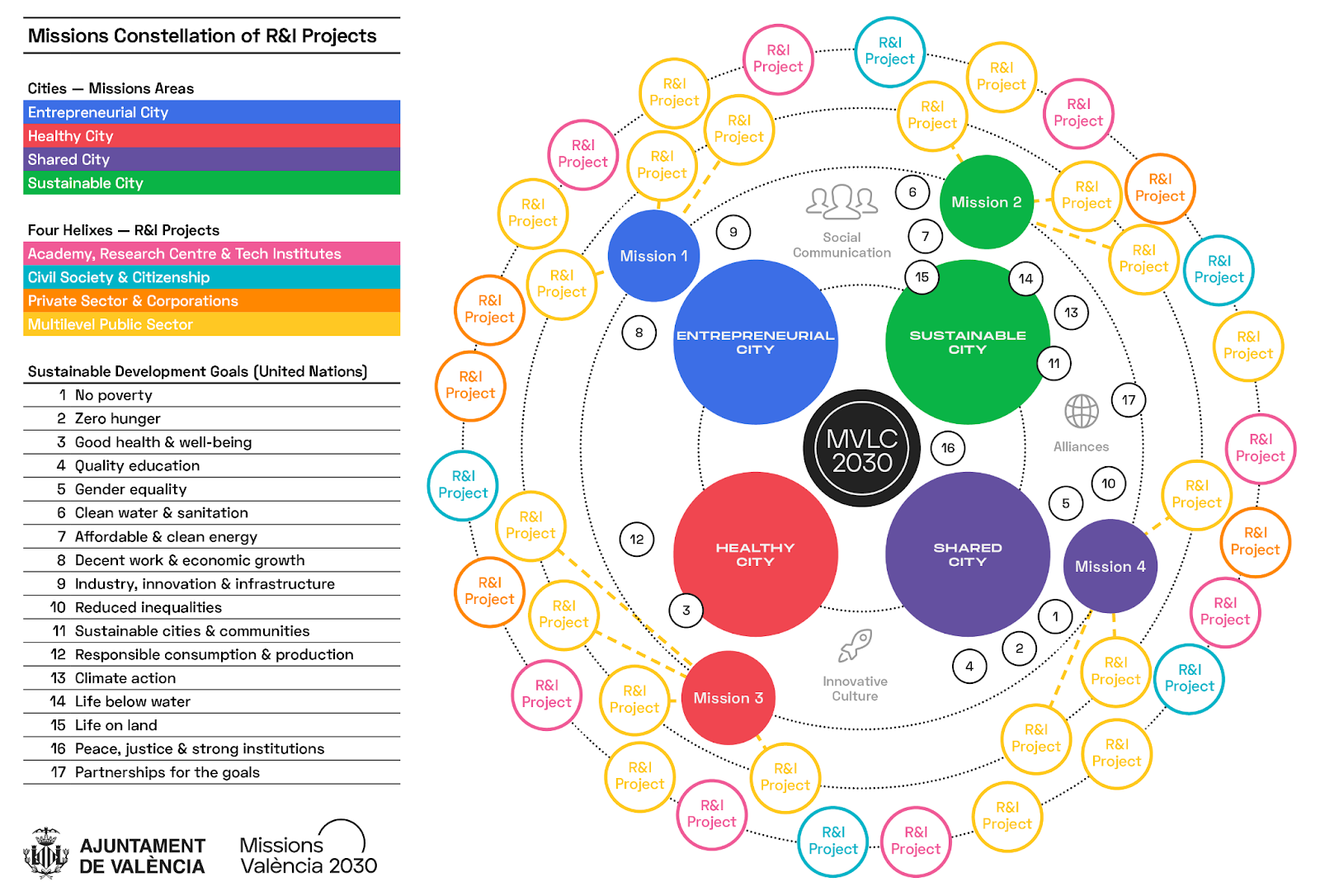

This is where planning and experimentation often come together. Identifying the change you seek to have is critical to being strategic with experimentation practice - there are many ways to define that orientation.

In terms of living labs, collective impact, portfolio approaches and several other forms of change initiatives, there is usually some form of "future vision" or challenge-framing which indicate the directionality, and often a cluster of domains or lenses through which experiments would be aligned and organised. For example, the Missions Valencia 2030 shows how experimentation is organised around a central challenge and several initiatives.

How change happens

This directionality - an agenda for change - is important for change initiatives. Not only does it focus energy and effort towards a range of outcomes, it helps bring people on board and sustains funding and engagement over time - the long hard work of change.

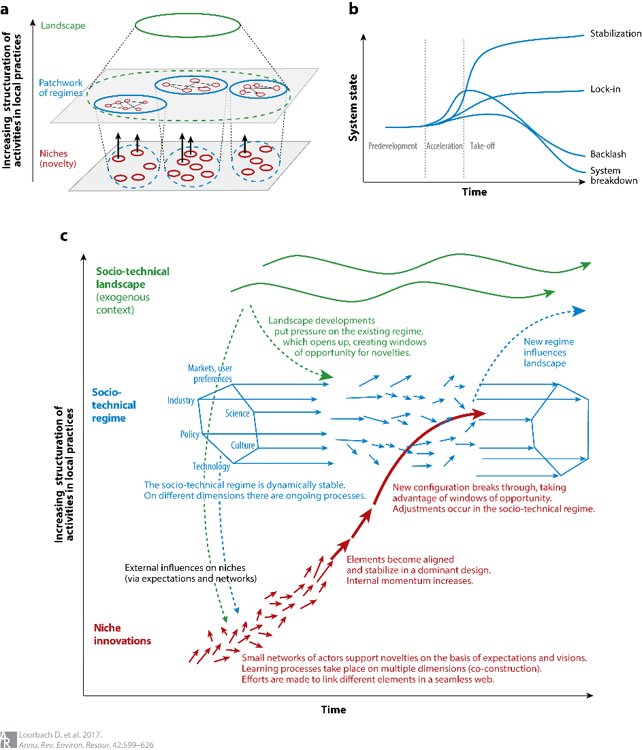

Alongside directionality is the importance of understanding (or more to the point, exploring and adapting to) how change happens, and what opportunities there are to influence that change.

The way I understand the dynamics of change is probably closest to the Socio-Technical Transitions space (which is primed well here by Derk Loorbach at DRIFT) with many options for where we intervene.

I would also reference the exploration of the 'transition framework' which Systems Sanctuary have been doing through the likes of their Powershift Framework and their recently released 'Art of Scaling Deep' research summary report (highly recommended):

In some spaces, you might consider developing a theory of change, a collective impact 'common agenda', building common ground or power analysis in movement building terms or even scenarios for systems change. Just remember that the map is not the territory...

“The map is not the territory”

- Alfred Korzybski

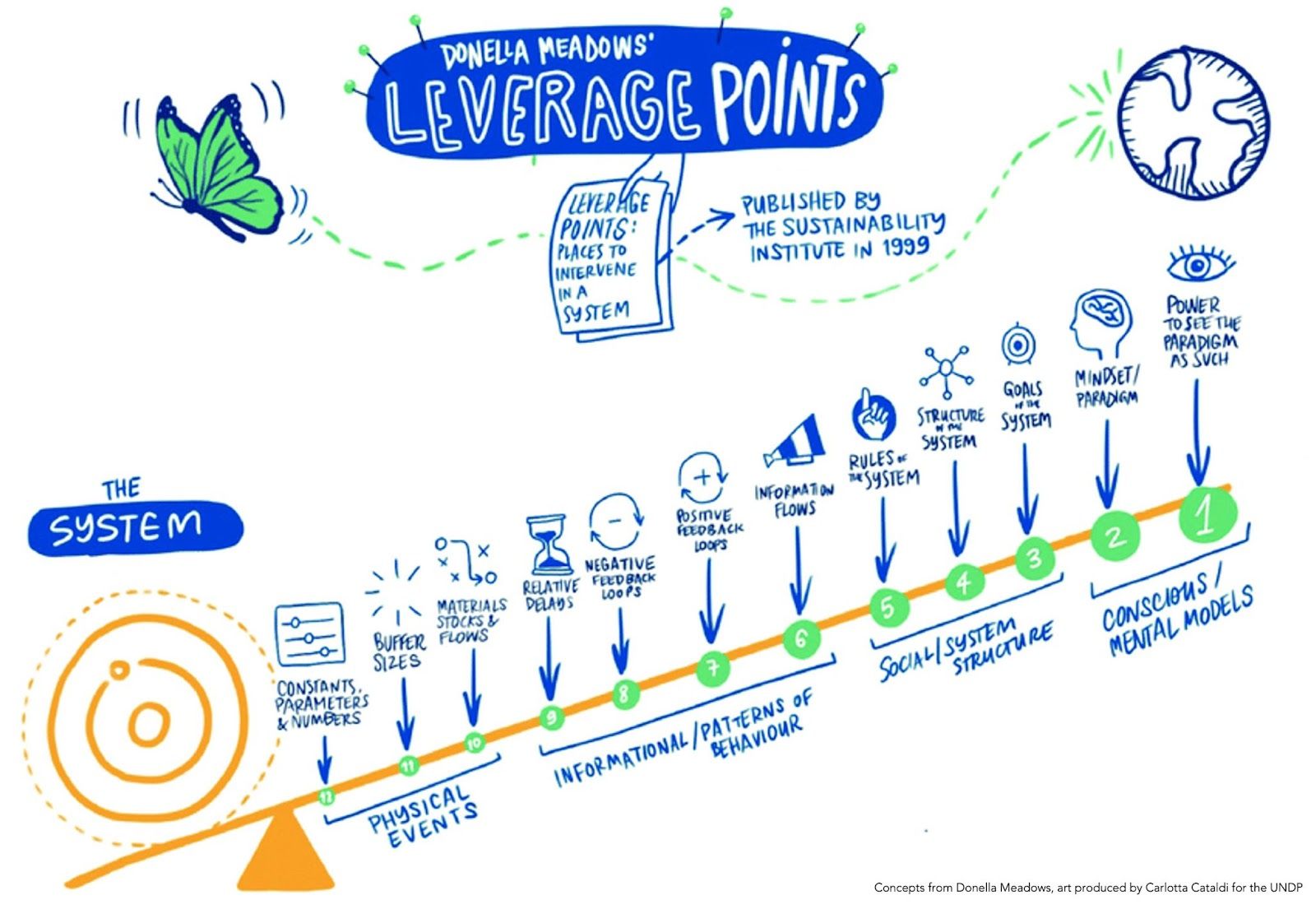

To influence change and make it durable (what some people might call "systems change"), we may need to operate on a number of levels. Here I would reference Donella Meadows' work around 'Places to intervene in a system':

[Side note: I worked with this idea in my Masters of Design, and co-developed a Strategic Leverage Canvas with a simplified four tier framing to support the design of portfolios of experimentation - you can read more about that here.]

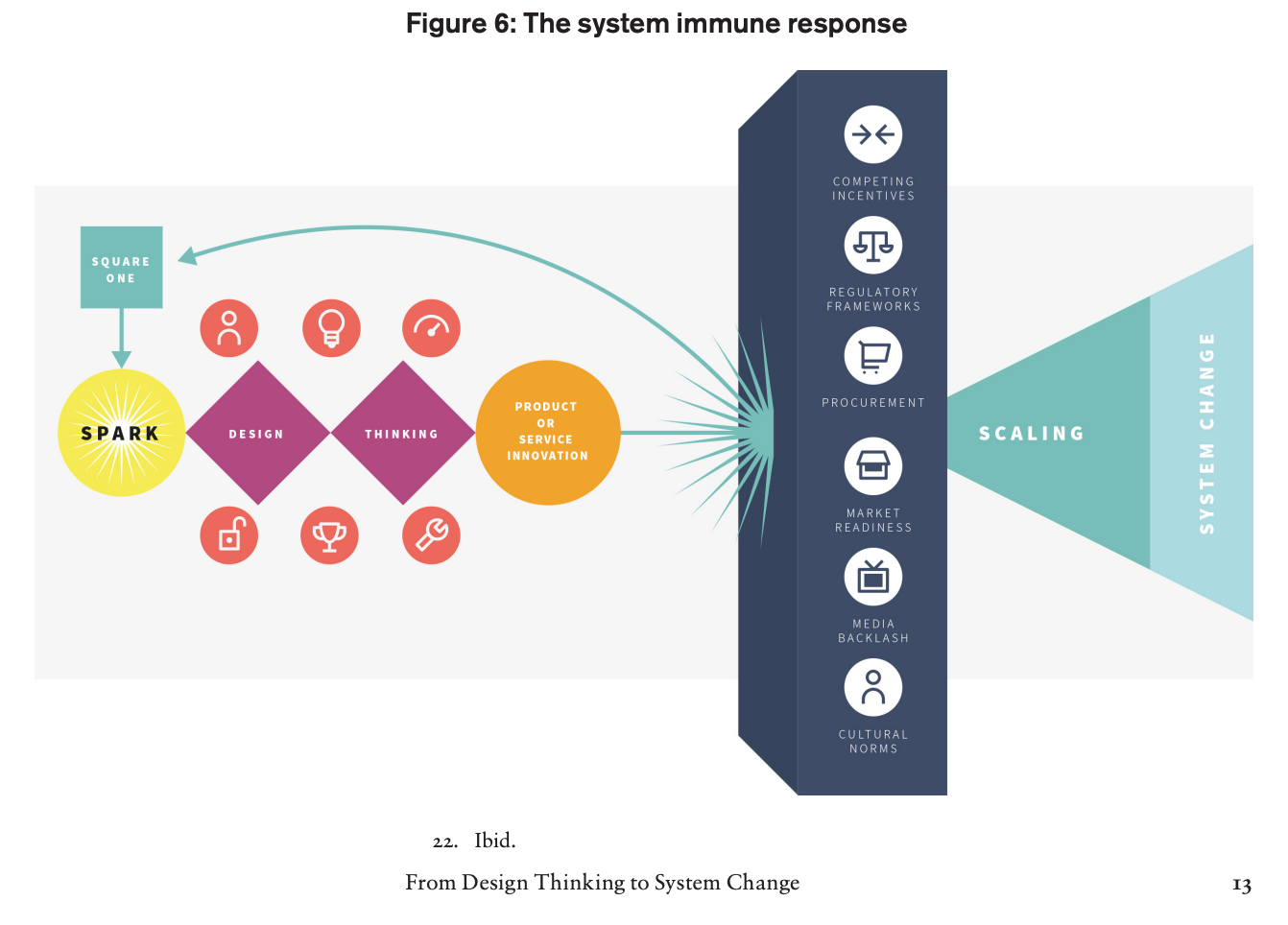

But let's not pretend change is a linear journey which can always be influenced (much less controlled) in the direction we hope for. Systems always have many actors, and factors like power, resources, resistance and the likes are always at play. I quite liked the simplicity of RSA's "From design thinking to systems change" in how they articulate the "immune response" which many of us will be familiar with:

Thinking about this on a broader scale, the Donughnut Economics Lab also published this useful video on Bill Sharpe's 'Three Horizons Thinking' which recognises not just decline, but also co-option by the dominant system, which is often ignored in models like "Two Loops" which is often cited in systems change spaces but is overly simplistic:

Often what we're doing by this point, is going down rabbit holes of assumptions.

We think we know what might happen if we intervene in the energy system by providing more electric chargers, for example. We might even have data about what happened in another context - like Europe. But what we know is, the longer the span of time our analysis and predictions are applied to, or the greater difference in the context.

From assumptions to experiments

This is the point that the work of designing experiments has its grounding - what we need to learn, test our assumptions about, explore specifics, or investigate how to grow and replicate what is working.

Experiments, as I conceive of them, are made up of:

- Context & Questions

- Methods to investigate these questions

- Measures to assess findings

- Reflections about what these findings mean

- Future areas of enquiry, based on these reflections

In the next post I will share some tools we're building to support people to build effective experiments, and how we aim to build a system through which we can track experimentation and our findings over time.