How We Use Experiments To Drive Insights

In this article, I outline how we developed an impact evaluation framework, and an experimentation practice which drove our ability to rapidly gain insight.

Learnings about the practice of running a Social Lab

In mature organisations we have standard measures of progress and success linked to consistently delivering a product or service.

These are largely irrelevant when you’re operating a Social Lab.

Yet that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t measure something.

So what should a social lab on a mission to improve youth wellbeing measure? What does success look like in the first two years?

Note: this post was written whilst working with Lifehack, however after 5 years we have closed the Lab. Get in touch if you’d like to know more about other ways we're continuing this work.

Finding Our Way To Running Experiments

When we took over Lifehack in 2013, we knew that there was a huge amount of ground needing to be made if we were going to shift the needle on the mental health challenges that young Kiwis were experiencing. But a scan of the ecosystem showed us that there was no simple answers — this is, after all, a wicked problem.

“If we don’t have a map showing us the way, we’re going to have to write one ourselves. We need a process to keep generating and actioning learning, to build clarity out of complexity.”

We knew from 5 years of running community initiatives, building startups, swimming in the social innovation space with Enspiral, that we needed a bias to action to generate those insights — not sitting around in an ivory tower and analysing endless reports.

We drew on our social entrepreneurial roots, and hit upon adapting the tools of the startup world to help us run a wide range of experiments about why,how and what we would be doing, to create tight feedback loops to inform our next steps. We reasoned that it would trim the amount of resource we wasted, speed up our learning, and give us some clear things to discuss with advisors and funders.

Success was clearly about the quality and quantity of insights we could generate.

So we began to use a process I first encountered in Ash Maurya’s writings about Lean Startup; Innovation Accounting. It was a simple process which fit the ‘Build, Measure, Learn’ loop, had a canvas associated with it, and Ash’s team had even built a tool to house the whole thing: LeanStack.

We had to make some significant tweaks; Innovation Accounting is incredibly business startup focused — especially in the language of how it is explained. However we simply thought about it in the way it was articulated by Eric Reis:

"To improve entrepreneurial outcomes, and to hold entrepreneurs accountable, we need to focus on the boring stuff: how to measure progress, how to setup milestones, how to prioritize work. This requires a new kind of accounting, specific to startups. " — Eric Ries

If you change ‘startups’ to ‘Labs’, and ‘entrepreneurs’ to ‘co-leads’, we felt this stuck. Essentially it was about navigating complexity, and working out where we could make the most impact with our resources available.

"Innovation Accounting effectively helps startups to define, measure, and communicate progress. That last part is key." — Ash Maurya

So after adapting the framework to focus on impact, we needed to create a framework which we would report against to our funder and stakeholders (ourselves being one of the harshest of all).

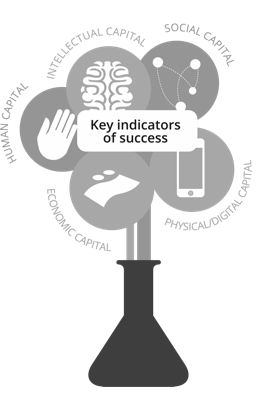

We called the framework the “5 Capitals” after reading Zaid Hassan’s book ‘The Social Labs Revolution’ which articulated what we were already coming to realise — evaluating on a narrow criteria like “how many digital projects have been created” would doom a project like Lifehack to failure without even getting started.

The Result Of Running Experiments

Implementing this experiment process dramatically increased the velocity of our learning and made communicating it much easier.

The experiment sheets showed the rigour with which we approached our work — it set us apart from any old team which could run around running events or “innovation processes”. It gave our stakeholders a reason to trust us.

I believe running a rigorous Experiment program was the single most important thing we did in the first 2 years of running our social lab.

The experiment sheets helped us visualise our progress and recognise where, when and why we were gaining momentum.

Whilst we were swimming in the complexity of setting up a lab and developing new interventions for a complex problem, we badly needed this as a grounding force for keeping us moving forward, even when the future was opaque. This Experiment culture became our sense check, as well as a process to systematically improve why, how & what we were doing.

Whether it was the physical stack of one page reports on our desk or seeing the experiments written up online, we had a tangible marker for progress. We also had a digital repository with snapshots of our learning, which became vital for sharing with our new team members as we began to expand and grow our lab.

I asked one of our advisors about how she saw our use of experiments, and it’s role in driving our social lab culture:

“I often talk about Lifehack’s use of experiments as being a systematic and reflective way to manage an unknown process. This is a new space, a new initiative. We don’t know what works, so we see everything we do as an experiment and we set it up as a learning cycle. So I talk to people about that as a “mode of working and being” when they are looking at setting up new initiatives, or heading out into the unknown in some way. Lifehack is my 'go to' example for heading out into the unknown and learning as you go.” — Penny Hagen, Smallfire & Lifehack Advisor

The Experiment Process In Practice

It’s easy to talk about running experiments, but in truth it takes commitment and discipline.

At times we felt like we were running at 1,000,000 miles an hour, and stopping to write up an experiment before and after felt like it would slow us down.

It doesn’t.

Running experiments sped us up.

Otherwise we were simply doing “heaps of great things”, but we didn’t have a process to hold us on track, give us a cadence, and make sure we were actually demonstrating learning.

Almost without a doubt, any time we were feeling off balance as a team, it was because we didn’t have the clarity of intention which running Experiments gives you.

Our Experiment Ground

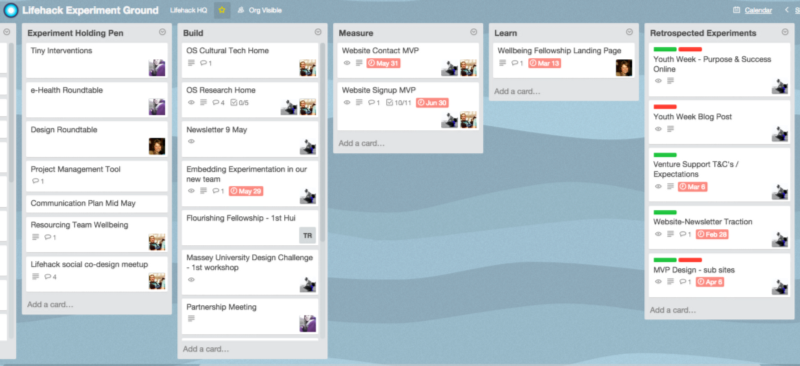

Having a hub where all the experiments live is a great way to see things visually. I mentioned LeanStack before — but we quickly out grew the 9 or so slots they had for completed experiments, so we moved to Trello. It’s a useful free tool which gave us the flexibility to set up our own digital space. At any one time our Experiment Ground might look a bit like this:

Each card represents an Experiment waiting to be run, being run, or completed.

Writing An Experiment

People often struggle to begin with, to know how big or small an experiment might be. I tend to flip it around, and think about:

What do you need to learn about?

How might you best learn this quickly and simply?

I suggest people start small and build complexity over time.

An example might be that we want to learn how we can best promote one of our events. In response, I’d write an experiment which tested 3 different channels: Facebook, Twitter and Print Advertising. The next time we ran an event, we might get a bit more nuanced, and write an experiment for the type of language we used. But we also scaled this up to whole initiatives we were running — such as a Lifehack Weekend — and we would assess the experience of people attending if we changed the format of the weekend.

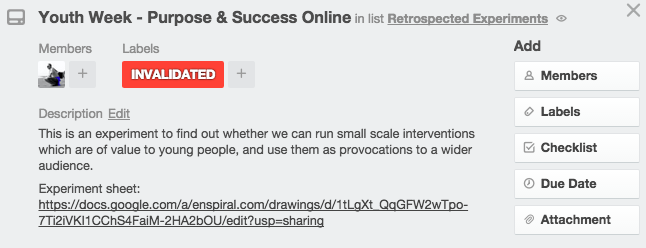

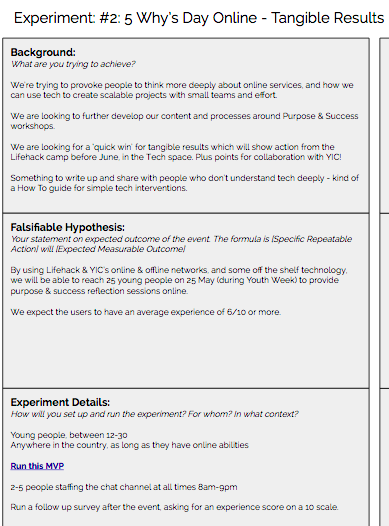

Here’s a practical example from a recent experiment we ran. I’m choosing this one as it was an experiment we ran expecting good outcomes and unexpectedly found that it was invalidated. It’s vital that when we’re operating in an experimental mode, we have to be open to our ideas failing.

This is what the Trello card looks like — so any one in our team can get a quick snapshot when browsing through:

When we begin to write the experiment details, we move it to the ‘Build’ section of our Trello board.

The Experiment Sheet is in two halves. The first half is what you writebefore actually doing anything in the ‘real world’. This is the thinking and planning time to set your intention for what you want to learn.

Here’s the first half I wrote for the Youth Week Purpose Check In:

I find these first 3 sections extremely valuable.

They force you to outline why you’re intending to do something (the background), how you intend on finding out whether you’re successful (Falsifiable Hypothesis), and what you will actually do to run the experiment.

We’ve got this down to about 15-20 minutes when we’re operating effectively. We also built in a step which gets the person who wrote it to run it past one of the team who can ask the hard questions — normally about the hypothesis, or about whether there’s a better / faster / cheaper way to get the same insight.

Running An Experiment

When the experiment is in play it moves to the ‘Measure’ column in Trello.

This is where the action is at. But all too often this is where people stop, thinking that they’ve done the learning by running the experiment.

Go out and do whatever it is you’re going to do to generate insight — put a prototype in the hands of users, run a workshop, send out a social media campaign, etc etc.

In the case of our Youth Week Purpose Check In experiment, we wrote our blog post, had our live chat operational, and were speaking to whoever showed up.

We're online today, ready to give you a free Purpose Check In! Do it now -> http://t.co/E90fcXAWdo pls RT @AraTaiohi pic.twitter.com/kIoP36YeXM

— Lifehack (@lifehackHQ) May 24, 2015

We've also got Kiran & Keniel from @NZYouthNetwork up at @GridAKL ready to give you a #YouthWeekNZ Purpose Check In! pic.twitter.com/rijom8FR6Y

— Lifehack (@lifehackHQ) May 25, 2015

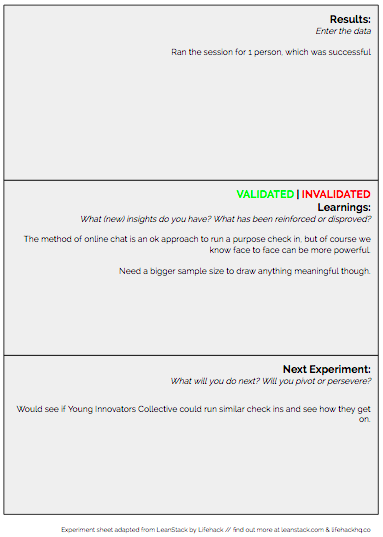

Retrospecting An Experiment

Learning from running the experiment is vital. This is where the second half of the Experiment sheet comes in handy.

We move the experiment card to the ‘Learn’ column on Trello at this point.

You can use all sorts of retrospective processes for this stage, or just stick to what’s in the sheet. We often used ‘Good / Bad / Change’ (from Agile) as a simple whiteboard session format to gain insights from a variety of people, then write it up on the experiment sheet after.

So the second half of our experiment sheet for the Youth Week Purpose Check Ins looked like this:

That’s right. One visitor. Despite setting up the experiment well, getting the word out fairly well, and having all the technical side ready to go — our experiment was invalidated as our Falsifiable Hypothesis stated:

By using Lifehack & YIC’s online & offline networks, and some off the shelf technology, we will be able to reach 25 young people on 25 May (during Youth Week) to provide purpose & success reflection sessions online.

Thankfully learning and insights aren’t binary.

What did we learn?

The method of online chat is an ok approach to run a purpose check in, but of course we know face to face can be more powerful. Need a bigger sample size to draw anything meaningful.

We found out that perhaps Monday during the day time isn’t a great time to run a check in for young people — our target group was largely at school or university. They may also not have heard about it, or remembered on the day. Perhaps the language we used didn’t gel with them? Perhaps we should have run a waiting list and just contacted people at a time more suitable to them.

The experiment, whilst invalidated (which really means “don’t do it in this format again”), was still useful, and it cost us virtually nothing to try.

“The value of running experiments isn’t in whether they have the outcome we expected or not, it’s in the detail of what happened when we run them.”

The team at Strategyzer also released this great blog post about running experiments. Well worth a read!

Managing Insights

We’re building a huge array of retrospected experiments which sum up some of the key insights we’ve had from running our program. When we’re operating at ‘Peak Insight’, they are the lifeblood of how we work — informing everything from our theory of change, to our year’s activities, to the language we use on our website and invitations.

The retrospected experiments act as a compendium of knowledge which we’ve gone out and tested for the specific context and community we’re operating with — not read about in a report somewhere.

Reading back over an experiment sheet is visceral, you re-live the experience, meaning that a huge amount insight more surfaces each time.

Pro Tip: we store all of our experiment sheets on Google Docs, linked to from our Trello board. It’s handy, but it’s not perfect.

Our Questions

We need your help and advice for this next part because PDF’s are where information goes to die…

We know that these sheets are excellent in the moment, and as references to go back to, but they don’t keep those rich insights explicit and visual in our everyday work. We’re looking for a physical or digital way of displaying these more visually, for our small team.

Have you had experience with knowledge management, complex design processes or innovation accounting?

How did you manage all the insights and keep them visual and relevant?

Please feel free to reply below, or send me a note on Twitter.

This article was written whilst I was a Lifehack co-Lead.

If you’d like to know more about this kind of (not-quite-scientific) Experimentation, I am working on a Field Guide to Experimentation Practice, written for Monash University but to be published in the creative commons soon. Just subscribe for more information.

You can also get in touch here for any clarifications.