On Sustaining Impact

This article is a plea to stop pouring so much resource into solely “getting ideas started” and then making them pitch for funding.

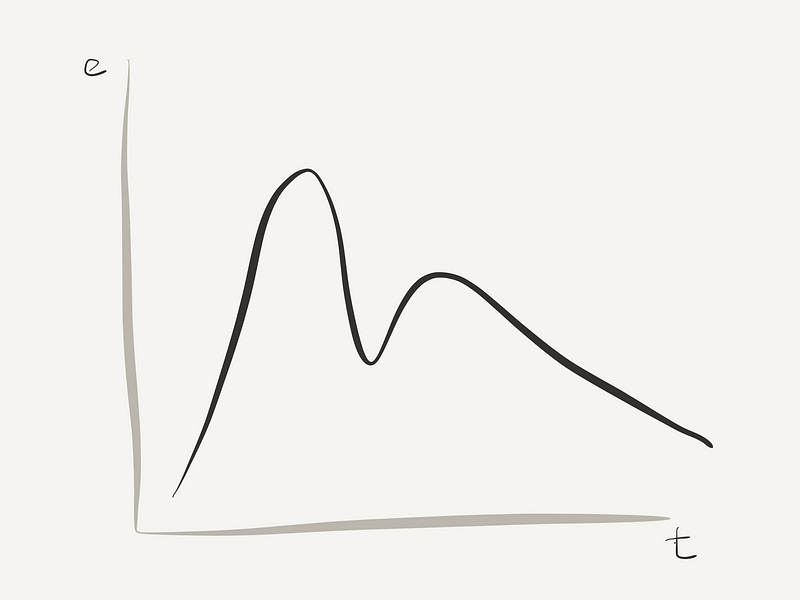

(yes, this image is tongue in cheek)

Dear Social Innovation Program Designers...

For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in what I would call the social innovation field. My work has spanned a variety of different initiatives; from living in rainforests working on conservation to being a founding member of a decentralised collective, co-founding a social enterprise food tech startup to co-leading a social lab on youth mental health & wellbeing.

My recent work included developing a community of practice for people working in and around social labs and complex challenges around the world and building experimentation practice in academic design research labs.

In that time I’ve been watching patterns.

Patterns of people starting new initiatives.

Patterns of people holding space for other people to start new initiatives.

Patterns of people trying to amplify the effort of existing initiatives.

Patterns of attempted collaboration... oft gone awry.

I would broadly categorise these observations as relating to; social entrepreneurs, Government & NGO intrapreneurs, program designers & managers, hackathons, design jams, accelerators, incubators, social labs, and mentoring programs.

Many of these patterns go something along the lines:

Many of you may have seen and experienced the same pattern — excitement, despair, improvement, and slow plateau to a quiet closure.

“The natural state of innovation, is failure.” — Josh Forde, Lifehack Advisor

I didn’t realise quite how prescient this was when Josh said it to me, but it has echoed through my observations over the last years.

The scale of the challenges we face are huge.

Whilst much good work happens at the grassroots, as a sector, we have a tendency not to be great at learning and sharing what works, and what doesn't.

This gets me thinking about designing better scaffolds to increase the likelihood of having a positive impact.

I watch the youthful zeal with which young social entrepreneurs head towards the latest ‘social enterprise accelerator’, backed by a well meaning NGO or Government. Sometimes they ‘graduate’ from their 9 weeks, with ‘bold ideas’ which they ask their friends, family, professional networks and perfect strangers to get behind, through crowdfunding initiatives, landing pages and social accounts. $10k, $20k later, and they’re “on track” with their bold ideas. But 3 months later, how many are still going? 3 years later? 10 years? These are the real timescales we need people working to make change happen.

Now replace ‘young social entrepreneurs’ with Government Intrapreneurs. ‘Social enterprise accelerator’ with ‘Design Jam’. ‘Crowdfunder’ with ‘Innovation Fund’. The formula still seems to hold. There’s huge churn rates with so many of these activities which we’re funnelling capital towards, in the hope they’ll generate some kind of ‘world changing idea’. It’s the Silicon Valley formula. The problem is, Silicon Valley has a weak formula for addressing complex problems (hell, they’ve got a few of their own at the moment…), in fact some argue they’re making it worse.

Does that mean we shouldn’t try?

Nope. That’s not an option that’s on the table. There’s too many big gnarly complex problems for that.

What I’m saying is that we’re getting better at learning how to rapidly recruit people with energy, provide them with a drum sticks and some tips on how to hit the drums, but we’re not providing any support to understand rhythm or play well with others in a band.

Many and organisations seem intent on protecting their “intellectual property”, even when the public purse has paid for the development of their impact initiatives.

I’m not suggesting that impact initiatives need more funding. Money is the common answer for many programs, be it an innovation fund, a ‘demo day’ to investors, or a matched crowdfunding campaign. Yet having funding doesn’t automatically mean the ‘bold idea’ will be executed well. Or that the team will stay together. It doesn’t mean the founders will make well informed decisions, despite their best intentions.

I’m talking about how we design these programs, and how we support what happens after them.

When I co-led Lifehack, we had the amazing opportunity to act experimentally, and we were rigorous with how we reflected on, evaluated, and analysed the kinds of interventions we created to support people to work on youth mental health and wellbeing. We tried a wide range of programs which all tied together into a community-centric social lab, which included; running weekend hackathons, modified hackathons with a paid team to build one of the ideas, 6 week bootcamp / innovation lab, 3–6 month fellowships, curated coaching and mentoring for teams with services in development, design challenges, and more. Yep, just about every buzzword under the sun. But very few people get the direct experience of running all of these in 2 years, and tracking the journeys of the people and projects which emerged.

Incidentally we also took public funding seriously enough to open source as many of those learnings, the evaluation and the design that went into the programs as possible. You can see the publications here.

So I humbly offer my reflections from 10 years or so of trying to have a positive impact and/or hold space for others to do the same, and viable strategies for the coming years of ‘impact accelerating initiatives’. I don’t suppose them to be a panacea, but with them, I hope we can develop some standards for what it means to scaffold people more effectively toward impact.

Program Design Patterns

During your initiative

These first three tips are for things to focus on in our programs and interactions where we hold space for others.

Design for agency.

When I boil it down, so much of people’s and team’s ability to get through, stay the course, and realise their vision, comes down to their agency. If they don’t really believe in the idea, or they don’t feel ownership of it, the likelihood is they will let it slide when the going gets tough. Whilst this isn’t surprising, it’s amazing how many programs are idea centric in their recruitment (“Have you got a great idea to change the world?!”), and incredibly light on critically questioning the participants on their reasons for doing it. This personal transformation work is hard, but in my mind it’s vital to getting people to do the work on their inner game, before hitting the ‘trough of despair’ and the ‘plateau of whatever’.

Design for relationships.

In a piece I shared a little while back, I argued that the true value of many of these initiatives, and the most lasting strategy, is to focus on the quality of relationships we’re nurturing. Why? Because these relationships are the glue for finding the solutions to challenges which lie in between us. Between disciplines and sectors. Between faiths and geographies. So when we’re designing our next accelerator, our next social lab, or our next conference — we need to be actively focussing on enabling meaningful connection and facilitating trust building, not leaving it for the coffee breaks.

Optimise for learning.

If someone has a bold idea which is likely to fail, what will they have left when that happens? Whilst many social enterprise accelerators are masters of drilling participants on their ‘social lean canvas’ and their ‘pitching skills’, these are often done rapidly, heavily facilitated, and in service of their idea. How many of these programs actually allow the space for people to reflect and embody these learnings? How many people who manage these programs actually understand how people learn (as evidenced by returns on $15bn per year in the Development sector)? I would argue that reflection and repetition are some of the most powerful approaches for really understanding what you’re being introduced to, so time should be made for this as a priority over ‘idea progress’. This is especially true where much of the content is new, or needs to be integrated into existing practices.

Beyond your initiative

Thinking about what happens when your initiative ends, is vital to not “creating a motorway into a brick wall” (thanks for that one Dave Moskovitz).

Consider the ecosystem.

Wherever you are in the world these days, there’s other initiatives online and offline which you will overlap with and be able to make use of. Mapping this, so that not only are you aware of what’s out there, but potentially what else people might be able to make use of beyond your borders, is shrewd. This map, in addition to the domain you’re operating in (e.g. mandate to look into policy interventions), can then help further define what you optimise your initiative towards.

Optimise for other support structures.

One of the strategies we used at Lifehack fairly successfully, was optimising our initiative toward getting teams ready for the next supported steps, because we knew they wouldn’t be ready to go it alone after only 6 weeks. Instead, we primed our program to give them the best chance at being selected for someone else’s program — in that case, a social impact accelerator. This can also be true for other initiatives — whether it’s heading into a mentoring program, a fellowship, a policy design lab, or some other form of supported pathway. It can also be true of having the explicit goal of transitioning the teams / services back into a supporting organisation. For these strategies to be effective, you have to know what your initiative is good at and what else is available, or specifically design it from the ground up and be open with participants about that.

Build your own pathway.

Many teams will benefit from some kind of coaching or mentoring beyond a highly structured program or initiative. Designing your own support program can allow you to be highly targeted with what content and advice is provided, what connections are made, and keep you closely integrated with the progress and impact of the initiatives. Whether you opt for low touch ‘monthly check in’ approach, a more sophisticated staged / gated model, or a very high touch concierge service & co-working model, there’s many different ways you can support people beyond an initial launchpad.

Build a community of purpose, practice and opportunity.

My ultimate suggestion is a community-based strategy which is akin to some alumni/fellowship type options out there, centralised around shared purpose. In addition to that, there’s a clear opportunity for developing a community of practice which may serve to develop standards, a knowledge commons, and/or important ‘relationship weaving’ to keep building social capital within the network of people. In addition to this, an additional layer which I haven’t seen effectively explored (other than unofficially), is for opportunities for people to gain livelihood and or other personal/professional opportunities for growth.

Summary

This article is a plea to stop pouring so much resource into solely “getting ideas started” and then making them pitch for funding. It's a plea to instead look closely at the qualities of how they’re developed, and how best to support them to have the positive impact their founders and teams strive for.

This ‘staying up’ phase is just as important, if not more so, than the ‘starting up’ phase, and is even more vital when we’re talking about social change and complex problems. We need to spend more time and resource on building multi-year platforms for experimentation, and less time building launchpads for rocket launches.

What I have observed as vital in the building of momentum and likelihood for success, is the ability for people to stay connected, openly sharing their insights amongst trusted peers, and enabling space for critical review and feedback. Whilst the initial ideas people work on may still plateau and fade away, if they can maintain the relationships, learnings, and build towards shared visions and opportunities — teams will form around better ideas and ultimately have greater likelihood for success.